Marina Teller, Professor of Private Law, Nice Côte d’Azur University, France

Draw me the law of the future

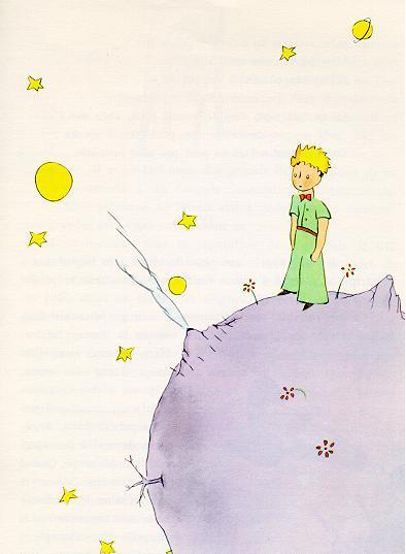

“Draw me the law of the future!”. Just like in The Little Prince, St Exupéry’s1 highly imaginative novella about a young intergalactic traveler, we wonder in this time of rapid and unpredictable change what the future will bring. As I study the intersection between the law and AI, I also wonder how the law and the legal profession’s role will change as we progress further into the digital age. And just as it is in The Little Prince, I believe that this is first and foremost a philosophical question.

“Draw me the law of the future!”. Just like in The Little Prince, St Exupéry’s1 highly imaginative novella about a young intergalactic traveler, we wonder in this time of rapid and unpredictable change what the future will bring. As I study the intersection between the law and AI, I also wonder how the law and the legal profession’s role will change as we progress further into the digital age. And just as it is in The Little Prince, I believe that this is first and foremost a philosophical question.

We would like to be able to tell this Little Prince that the law of the future will be different, because it will be re-invented. And that, as our utmost wish, we would like to be able to guarantee that it will be better – that we will have a “brave new law”.

The world of tomorrow, a digital world open to AI, is definitely a new world, and its future lies somewhere between our hopes and our fears. Both scenarios exist and both outcomes are therefore possible. There are many people who fear the worst, and who are already warning about the potential negative consequences of the combination of the law and AI. But let’s take the risk of imagining the best. “I’m a pessimist because of intelligence, but an optimist because of will.”2 The future offers us all the possibilities, so let’s be optimistic, by will, and re-imagine tomorrow’s law.

The digital world and AI make us better beings, in a way. Indeed, because they force us to think about what we didn’t think, to ask ourselves new questions and to question ourselves about our essential values. What is a human being? How can we preserve humanity? How can we maintain both ethics and the rule of law? These are the questions for us now, but also for tomorrow’s lawyers.

Thinking the ‘unthought’

We cannot shy away from these questions; we have to think these unthought-out things to their conclusion. This is necessary because, as we know, in the future technology will have unprecedented potential and power over us – including the potential to render mankind obsolete.3 But while we can’t predict the course of history, we do know that human agency is paramount, and that history is ultimately made by human will4 and the decisions that we make. So, we have no choice. We must go forward and try to reinvent law for the digital age.

I believe that tomorrow’s law will be better and more inspiring (at least we must do everything to ensure that this happens). Why do I hold this belief in the face of voices who claim the opposite? Because we have faced challenges many times before in human history where new technology has changed our lives and our destinies, and there are many of our colleagues around the world who now recognize the dangers and are working for a better digital future. The future forces us to question our present because we know that digital transformation is unstoppable. The future is actually with us now – it is what we decide now about the future that we want for our children and their children that will ultimately invent the future for them.

Questioning our actions, our interactions and our deepest being

Let us silence the pessimists. But let us also be clear: the challenges we face are immense. Technology has an unprecedented potential for destruction that could wipe out our institutions, our privacy, our free will, our freedom of thought and even our integrity as human beings. We must be constantly aware of the potential impact of transhumanism,

which promotes the transformation of the human condition by using advanced technologies to modify or enhance human intellect and physiology. We cannot ignore these challenges. Nonetheless, I see them as obstacles to be overcome and opportunities to create an “augmented law”, which will suit future “augmented men”, if in fact they become so.

Law, as a social regulator, must bring new rights, in order to protect the fundamental values of our society: to take into account new vulnerabilities so that AI is not a job-killer but a provider of new jobs, to offer everyone equal access to culture and education, to make sustainable development and the fight against global warming a reality. These are major challenges, but we know that technology can bring real solutions through the appropriate use of digital tools, connected objects, sensors, and the application of AI in agriculture and more broadly across society in the green tech revolution.

It is now up to the legal system, and those working within it, to provide the legal framework to prevent disaster scenarios. We need to avoid data collection and big data analytics giving rise to generalized surveillance that would spell the end of democracies; we must avoid “technological solutionism”5 and build ethical and legal boundaries to technologies that enhance humans. In other words: the law will need to set rules to protect what is human in us all.

The law will have a difficult but magnificent mission of the utmost importance: to preserve fundamental human rights. This will require us to go beyond our current understanding, by imagining “future digital human rights” and “technologically sustainable development”. I can foresee a time when governments will need to pass specific laws in order to prevent fundamental discrimination related to algorithmic bias. We are seeing new applications of big data and AI emerging: for example, in the medical field, where the use of health data could revolutionize the treatment of certain diseases. However, these new applications will require a legal framework for data access and processing which goes beyond what we have now

to ensure that personal data can be shared for the purpose of medical research. Lawyers will have to focus on the transition from big data to smart data, while ensuring that individual privacy rules are respected.

Towards cyberjustice

I am convinced that digital tools will transform tomorrow’s law.6 Cyberjustice is no longer a myth.7 AI can replace humans in decision-making. While neither judges nor lawyers will be replaced by robots, AI will be a tool to assist them in decision-making, which can lead to a judicial decision through the use of legal data analytics. We have an opportunity to transform the law through this technology, to guarantee its effectiveness and reduce the cost to litigants, many of whom may have given up exercising their rights because of the cost and slowness of justice.

AI’s contribution to the administration of justice8 is a game changer for legal knowledge and practice. New balances will have to be found in the distribution of power between technology and humans. The law will have to draw lines between the decisions that can be made by algorithms and those that cannot. It will therefore be necessary to rethink fundamental values and principles that will remain the prerogative of humans. It is at the heart of technological devices that the next battles will be played out: lawyers will have to find the art and the way to introduce the values held by law into these devices. The aim is to create a technology that will guarantee rights by default, thanks to new principles: equality by design, equity by design, compliance by design. Tomorrow’s lawyers will need to work alongside coders and data scientists to perform these tasks. The development of a common language between the law and data science is an exciting prospect for all those who believe in sharing knowledge and who view human intelligence as a collective phenomenon.

May the future of the law strengthen this optimistic and reinvented vision of the future.

1 Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Le petit prince, New York, Reynal & Hitchcock, 1943.

2 Antonio Gramsci, Gramsci’s Prison Letters, Columbia University Press

3 Physicist Stephen Hawking said the emergence of artificial intelligence could be the “worst event in the history of our civilization.”

4 https://www.cnbc.com/2017/11/06/stephen-hawking-ai-could-be-worst-event-in-civilization.html

5 Gary Olson, in Pessimism, Optimism and the Role of Intellectuals, 2019

6 Evgeny Morozov, To Save Everything, Click Here – Technology, Solutionism and the Urge to Fix Problems That Don’t Exist, Allen Lane, 2013. See also: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2013/mar/09/evgeny-morozov-technology-solutionism-interview

7 See : Tania Sourdin, “Reimagining Justice with AI Technology”: https://youtu.be/JpX7Pm71cewhttps://www.cyberjustice.ca

8 https://www.cyberjustice.ca See the remarkable work of Karim Benyekhlef, professor at Montreal University. See Kevin Ashley, professor of law at the University of Pittsburgh, Karl Branting, Chief Scientist in charge of the Machine Learning for Computational Law project at MITRE Corporation and Tom van Engers professor of law at the University of Amsterdam: https://youtu.be/rJfCP_JQVs0

Marina Teller is a professor of private law at Nice Côte d’Azur University. She leads a master’s degree in banking law and fintech and a research program called Deep Law for Deep Tech with Frédéric Marty (CNRS). She also runs a 3IA Chair dedicated to smart technologies and AI. Her work is at the crossroads of deep technologies and law; how blockchain, smart contracts, AI systems and connected objects have important consequences for the legal system. Her research focuses on the regulation of algorithms (“An illustration of technological risks through algorithmic biases,” Law and Connected Objects, The law and connected objects,2020 <halshs-02952872>; “Ethics and AI: A Preamble to Another Right,” Bank and Law,2019. <halshs-02952902>; “Artificial Intelligence,” Economic Law in the 21st Century,2020. <halshs-02952852>; “The advent of Deep Law (towards a numerical analysis of the droit? ) Mixes in honour of Professor Alain Couret, <hal-02550489>

Marina Teller is a professor of private law at Nice Côte d’Azur University. She leads a master’s degree in banking law and fintech and a research program called Deep Law for Deep Tech with Frédéric Marty (CNRS). She also runs a 3IA Chair dedicated to smart technologies and AI. Her work is at the crossroads of deep technologies and law; how blockchain, smart contracts, AI systems and connected objects have important consequences for the legal system. Her research focuses on the regulation of algorithms (“An illustration of technological risks through algorithmic biases,” Law and Connected Objects, The law and connected objects,2020 <halshs-02952872>; “Ethics and AI: A Preamble to Another Right,” Bank and Law,2019. <halshs-02952902>; “Artificial Intelligence,” Economic Law in the 21st Century,2020. <halshs-02952852>; “The advent of Deep Law (towards a numerical analysis of the droit? ) Mixes in honour of Professor Alain Couret, <hal-02550489>