by Vicki MacLeod, Secretary-General, GTWN

by Vicki MacLeod, Secretary-General, GTWN

Facial recognition technology is being deployed in an ever- expanding number of applications around the world – from passport screening at airports, to surveillance of employees in workplaces, to the police and court system, and even in behavioural research. But should we embrace this technology as a brilliant solution to security and identity veri cation requirements, or should we be more concerned about the impact on individual privacy and data security?

At its iEXPo2017 conference in Tokyo, nEC demonstrated the many bene ts of its advanced, real- time facial recognition technology” which is widely acknowledged to be one of the most sophisticated and reliable systems that is available worldwide. But despite impressive advances in this technology, the response by some media focussed on the potential impact on the individual of being constantly watched over and monitored by unknown observers.

There is an increasing number of new applications of facial recognition technology in a surprising variety of industries and circumstances. For example, it is being used at Crown Casino in Melbourne to identify VIP gamblers as well as banned guests. Australian state and federal policing agencies are also deploying it, with South Australia Police using it to identify criminals and to search for missing persons. And it is reported that the northern Territory Police, in the far north of Australia, is using the technology to identify unconscious people admitted to hospital and those who are suffering from Alzheimer’s and may not be able to remember their own identity.

Perhaps of more concern to privacy advocates is that employers are beginning to deploy facial recognition, combined with arti cial intelligence, to monitor and evaluate the mood and attitude of staff. one such example is Westpac bank, which has said it is using this approach, so that managers can intervene and counsel individuals if necessary.

Retail giant West eld is using small cameras fixed atop advertising screens and using software developed by French company Quividi to detect individual faces to estimate the age, gender and mood of shoppers in its malls1. West eld also tracks shoppers’ movements by pinging their Wi-Fi enabled devices with routers littered across its centres. West eld claim it can only detect faces at this stage, not identify individual shoppers. West eld is now also deploying number plate recognition in some of its car parks, which in theory could at some future time be matched to individual shoppers, their home address and their demographic data. Privacy advocates are concerned that the trend for monitoring individual behaviour in public places will only increase, and have called for more transparency by companies about the purpose of the surveillance so that individuals are aware how and why they are being tracked and what the data is being used for.

Facial recognition is also being increasingly used in the sporting and entertainment context to monitor crowd behaviour and to verify individual identity. The Tokyo 2020 olympics will use facial recognition technology to streamline the entry of athletes, of officials and journalists (but not ticket holders) to the games venues. In response to the increasing threat of terrorism, organisers are proposing to use facial recognition in order to prevent attendees from lending or borrowing ID cards. In October 2017 the Justice Ministry deployed facial recognition technology to screen passengers at Tokyo’s Haneda airport.

Facial recognition is also being increasingly used in the sporting and entertainment context to monitor crowd behaviour and to verify individual identity. The Tokyo 2020 olympics will use facial recognition technology to streamline the entry of athletes, of officials and journalists (but not ticket holders) to the games venues. In response to the increasing threat of terrorism, organisers are proposing to use facial recognition in order to prevent attendees from lending or borrowing ID cards. In October 2017 the Justice Ministry deployed facial recognition technology to screen passengers at Tokyo’s Haneda airport.

The Australian federal government has established a National Facial Biometric Matching Capability, known as “The Capability”, to enable law-enforcement agencies to share more easily the identity photographs they hold. Meanwhile, the Australian Department of Immigration and Border Protection, uses NEC’s NeoFace technology in its departure SmartGates, which are located at all Australian international airports. NeoFace measures the distance between the eyes, the width of the nose, depth of the eye sockets, shape of the cheekbones, and length of the jawline in order to make a positive match. Similar software is already deployed at a number of other airports around the world, including at JFK and at Heathrow.

In October 2017, all Australian state and territory governments agreed to allow the federal government access to driver’s licence photographs, allowing for much easier inter-agency sharing. In the Capability, these will be added to a searchable collection of passport and visa photographs. The database is to be used for looking back over CCTV to identify suspects, but privacy advocates are concerned that in future the system could be used for real-time tracking of anyone entering sports stadiums or malls

Bloomberg news reported that Russia was adding facial- recognition technology to some of its network of 170,000 surveillance cameras in a move to identify criminals in real-time. China too has been working on a facial- recognition system since 2015 to identify any one of its 1.3 billion citizens in 3 seconds but has apparently been encountering some issues, including concern about whether there is a real need for some systems. For example, the Wall Street Journal has reported3 that on Chongming Island near Shanghai, a new running course has been out tted with a facial-recognition system to ensure runners don’t take shortcuts through the foliage during timed competitions.

Bloomberg news reported that Russia was adding facial- recognition technology to some of its network of 170,000 surveillance cameras in a move to identify criminals in real-time. China too has been working on a facial- recognition system since 2015 to identify any one of its 1.3 billion citizens in 3 seconds but has apparently been encountering some issues, including concern about whether there is a real need for some systems. For example, the Wall Street Journal has reported3 that on Chongming Island near Shanghai, a new running course has been out tted with a facial-recognition system to ensure runners don’t take shortcuts through the foliage during timed competitions.

There may be other problems with the accuracy of facial-recognition technology, as it does not always work accurately. At London’s Notting Hill Carnival in August 2017, human rights advocates group Liberty observed its use by London’s Metropolitan Police. According to Liberty, it couldn’t tell the difference between a young woman and a balding man and falsely matched 35 people, ve of which were pursued with interventions, meaning innocent members of the public were stopped who had, police later discovered, been falsely identi ed. Liberty claims that this raises the real risks of unfettered use of facial recognition technology in a democracy.

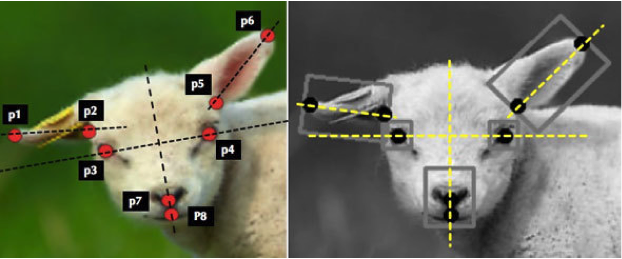

But for every concern raised about facial recognition technology, there are other stories about the incredible insights it can provide into behaviour. It is even being used in research into animal behaviour, in order to improve animal welfare and our understanding.

Source: Estimating Sheep Pain Level Using Facial Action Unit Detection by Yiting Lu, Marwa Mahmoud and Peter Robinson Computer Laboratory, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK

A group of researchers at Cambridge University4 have been using facial recognition technology to assess pain levels in sheep, which is a crucial, but time- consuming process in maintaining their welfare.

In summary, there is no doubt that the growing use of facial recognition technology, especially in an unfettered and hidden way, does raise concerns about the potential impact on individual privacy and the sense of community that is fundamental to a free democratic system. on the other hand, its increasing number of applications demonstrates its value in providing insights into human, as well as animal, behaviour, and solutions to some very dif cult challenges in modern society. The issue is one of transparency on the part of the users of this technology, and knowledge on the part of individuals and communities, so that the bene ts of the technology are balanced with safeguards against unnecessary or reckless application.

Vicki MacLeod is Secretary-General of the Global Telecom Women’s Network (GTWN) and editor of the GTWN’s flagship publications. She is a global strategic adviser with many years’ experience in the telecommunications industry and government policy areas, both in Australia and internationally.