Derrick de Kerckhove and Maria Pia Rossignaud, TuttiMedia / Media Duemila

We have entered a new era of human evolution. Since the end of the last century human beings have been delegating their faculties to machines, first to the computer then to the cell phone and now to Artificial Intelligence. Human societies around the world are faced with harmful and dangerous misinformation on the one hand and, on the other, the ability of GPT to produce human discourse without awareness or responsibility for what it entails. We are thus reaching the pinnacle of the epistemological crisis that we have already predicted and foretold in many articles published by Media Duemila, the primary Italian magazine about digital culture.

The EU’s Media Freedom Act1 is a response to increasing concerns about the politicization of the media and the lack of transparency of media ownership. It seeks to put in place safeguards to combat political interference in editorial decisions and guarantee media freedom and pluralism, as the basis of democratic life.

What to believe: the exponential growth of information

Information has always been a feature of human activity. In more recent times, information has been expressed by human beings, produced by machines and then processed by information technology. Understanding the links between the information and the eventual message has been made increasingly difficult by the enormous growth in complexity in social, economic, political, cultural, industrial, and scientific fields. Now human society is generating an entirely new organism, driven by an incredible increase in information flows. While this could lead to a much richer and more powerful body of knowledge, it may nevertheless also degenerate into a disordered and damaging cancer.

It is therefore no surprise that people all over the planet have become both fascinated and terrified by generative AI. Humanity is entering an era of unprecedented doubt: what to believe?

Real vs fake

The response to two award-winning photographs illustrates the increasing difficulty of distinguishing the real from the fake.

The first is the 2023 World Press Photo of the Year by Ukrainian photographer Evgeniy Maloletka2: the missile strike on the Mariupol Maternity Hospital in November 2022, which led to the death of Iryna Kalinina and her stillborn son Miron. The official Russian media immediately claimed it was a fake photograph doctored by Ukrainians. The denial of authenticity to the World Press winner is standard behavior to be expected from Russian State media. It is part of the general panorama of fake news and denial of evidence to which the world has become accustomed since social media began to be used for political and business purposes.

The story behind the second image, on the other hand, is another matter altogether3. German artist Boris Eldagsen turned down the award in the creative section of the 2023 Sony World Photography competition, confessing that the now famous picture of two women – “Pseudomnesia: The Electrician” – was not a genuine photo, but one concocted by a prompt to a cleverly creative software. Eldagsen explained to the press that he refused the award, not out of remorse for having fooled the jury but to bring attention to the present and immediate danger such a potent technology as AI driven photography could become in a world already attuned to the production and circulation of effective – and lucrative – politically or personally damaging persuasion.

As regular consumers of photographs both private and public, this was a shocking eye-opener for us. For years, like most of our contemporaries, we had been used to accepting photography as a reflection, representation, and guarantee of the veracity of events and physiognomies. Yes, of course, as other media scholars, we were aware of the many critical approaches to the “illusion of reality” thanks to which people generally trust photography. But this creation of ‘reality’ ex nihilo was something else altogether. Our trust in photography has been shattered forever. In other words, the sudden arrival of photography in the category of questionable evidence was equal to the breaking down of the last wall of defense that we had unconsciously erected to protect objectivity from subjective erosion and distortion. Eldagsen’s courageous move should be a fair warning to journalists worldwide and in the European Union in particular.

Language as an operating system

Anybody who, for whatever reason, has had to migrate from Windows to Apple OS, or vice-versa, knows how tedious, difficult, and time-consuming this can be. For some, like us, it may take weeks to get fully adjusted even if you have already had over 40 years’ experience of using personal computers. Imagine then how much more painful the same transition is when imposed on a whole culture. And yet, that is exactly what is happening to the world’s various cultures today. And this is not just a software issue, but a transformation of the whole basis of human civilization – a rapidly accelerating switch from human literacy to machine-driven algorithms.

Language is the main operating system of any community. It is through linguistic exchanges that a community, from the family unit to the clan and the tribe, sets standards and rules of behaviour that affect religion, education, local practices etc. That is not really news because no-one would seriously doubt or play down the role of language in organizing human societies.

Context and meaning

The question becomes a lot more precise when the metaphor of an operating system is applied to writing. The difference between, for example, phonological systems, like western literacies and iconic ones, like Chinese, are well-documented and make intuitive sense. Reading English doesn’t require anything other than knowing the sound of the letters and the language itself, while reading Chinese doesn’t require you to know the language but rather to be in a position to guess the meaning of the icons according to the right context for whatever language is being used (and there are more than 80 different languages in China). Putting the text before the context or vice versa define two very different operating systems that affect and condition the cognitive processes of the reader.

Less obvious, but still critical are the different cognitive approaches needed to read Latin or English in comparison to those used to decipher scripts without vowels, such as Arabic or Hebrew. There again, the context must come first, merely to enable the reader to decipher the text. A better understanding of such differences would go some way to explaining some of the key features that distinguish Western and Eastern civilizations. But that is not the present purpose of invoking the theory. The question is rather: what are key features of a society that transitions from being run and ruled by linguistic operators to one that delegates its decision-making processes to algorithms and AI?

The first and perhaps most important feature modification is that, perforce, language works by, with and through meaning. Algorithms simply don’t. Anyone who has used automatic translation knows that neither Google nor Deepl.com (another excellent translating software) knows any language at all. It operates iconically by matching answers to queries and selecting the best option by statistical ranking. That is pretty well how chat GPT and the others work. Of course, the analytics obey simple instructions provided by humans, and, at first, supervised by data scientists, but the lightning advances made by successive generations of GPTs come from the possibility of trusting the instructions to be sufficiently precise to allow from the program to download and sort humongous amounts of data ‘unsupervised’, thus saving thousands of years of human labor. The present quantum leap of AI is owed to that step and to the advances made by machine-learning and computing processing power. All to the good? Yes, but…

The siren call of the LLM

The problem with a machine providing usable and circumstantial answers to our questions is not that they may not be good enough. Quite the contrary, the problem is that they may be too good to ignore. The temptation to use them will not abate in view of the phenomenal progress the Large Language Models, or LLMs, have made in a very short time. It may make perfect sense for humanity to take advantage of all the inputs it has made into the collective heritage of human intelligence and memory since the Internet was first made available to you and me, that is, January 1st, 1983.

We can collectively reap the benefits of decades of human discourse online, some of it banal, inconsequent, or deliberately misleading, but most of it filling valuable data banks. Overall, there seems to be little wrong and much right going along full steam with such an unexpected opportunity. The question then becomes: are we really ready to change our operating system from dialectic, deliberative and reflective to quasi-oracular? Are we ready to demote language from being our main mass medium and to delegate our cognitive functions and strategies to automation? Can we afford to let algorithms become the accepted authority and enable them to claim objectivity?

A loss of individual expression

Language first and later writing have allowed people for millenia to operate a good part of their lives on their own, provided they conformed to legal and social guardrails. Letting machines think in your stead will not guarantee that this opportunity continues. Some scholars, such as Paolo Benanti, talk about the foreseeable ‘loss of competences’. This may cover specific skills beginning with the proper or pertinent use of language itself. Journalists are known to be among the principal users of LLMs. It saves them time and guarantees linguistic correctness, a vanishing skill. Even before any direct intervention from LLMs, we have already observed a general trend in school, online, and even in print material, to lose, downplay, or ignore grammatical and orthographic skills. This neglect of the right word or the right spelling translates into a loss of individual power, not to say of individuality itself. Indeed, although addressed to individual queries, LLMs operate like a collective cognitive system. So does language, by its nature, the difference being that language and writing work their ways within the mind of the individual while LLM do that work from the outside of human bodies. Then there is an ethical as well as a cognitive issue, that is, of responsibility. Humans stand behind their words. If it is found that they don’t, they are held to account by law and shunned by their peers.

Language is being detached from reality

So, how does all the above announce an epistemological crisis? It’s all about language. Whether spoken or written, language is not in itself a way of thinking, it is only a code. Like photography, writing is not ‘reality’ but a representation of it. Many people, however, take the oracles of GPT for the expression of thought, just as they take photography for the representation of reality. Of course, informed people do not make that mistake but combined with the onslaught of fake news and science denial, automated simulated thinking detaches language from its association with authentic reporting. Overtaken by algorithms as a system for decision-making, language is demoted to an auxiliary role. It loses its function of guaranteeing a reliable attempt at presenting ‘reality’ in context. In that turmoil a clear distinction between objective and subjective is gradually disappearing. The result is that using words and sentences turns into a ‘free-for-all’ information system run by anybody, anywhere, with any media.

- https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press- releases/2023/12/15/council-and-parliament-strike-deal-on-new-rules-to- safeguard-media-freedom-media-pluralism-and-editorial-independence-in-the- eu/ ↩︎

- https://www.worldpressphoto.org /collection/photo-contest/2023/ Evgeniy-Maloletka-POY/1

↩︎ - https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2023/apr/18/ai-threat- boris-eldagsen-fake-photo-duped-sony-judges-hits-back ↩︎

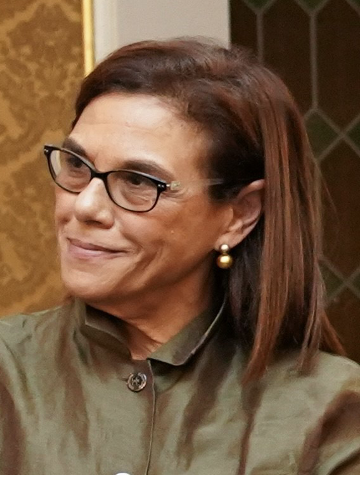

Maria Pia Rossignaud is Senior Vice President of the Osservatorio TuttiMedia, publisher of the first Italian digital culture magazine “Media Duemila”. Dr Rossignaud is a journalist expert in technologies applied to media and society. Italy’s President Mattarella awarded her with the honor of “Knight of Merit of the Italian Republic”. She is among the twenty-five digital experts of the Representation of the European Commission in Italy. Her publications anticipate and analyze the effects of the digital transformation on political, economic and cultural affairs. “Beyond Orwell: the digital Twin” is one of her widely commented books. Also concerned with the status of women she sits on the board of “Stati Generali delle donne”, and she is involved in the GTWN (Global Telecom Women’s Network). She has been professor at LUISS University – Sapienza – IULM. And she involved as speaker in many international conferences on digital transformation media, communication and advertising.

Derrick de Kerckhove is a journalist at Media Duemila. He has spent many years as a professor and cultural researcher in digital media and digital transformation of society in both Canada and Italy. He is a former long- term Director of the McLuhan Program of Culture and Technology at the University of Toronto.